What Happens When Bigger Isn't Better

The end of the scaling era and why this could be a great thing

Recently, one of AI’s most well-known and mysterious1 figures, Ilya Sutskever, uttered words that made groups of AI researchers around the world break out into cold sweats, "results from scaling up pre-training … have plateaued."2

The fail-proof, too-good-to-be-true, method of improving Large Language Model performance by increasing parameters, training data, and training time has stopped proving effective. And to be honest, it was incredible it worked as well as it did.3

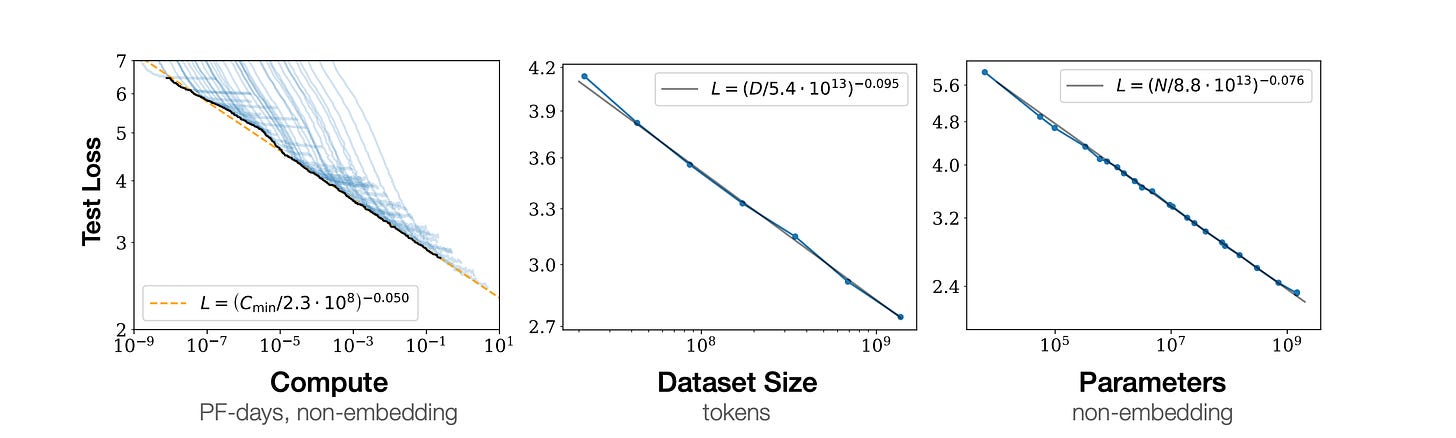

Kaplan et al.’s figures which beautifully highlighted a power law relationship between test loss and compute, dataset size, and parameter count may be ones we reminisce about for decades to come.

So … what now?

Well there are a number of things we could expect to see.

How development priorities may change

Perhaps most intuitively, we can expect attention to be redirected to alternative performance improving pursuits. With brute forcing improvement gains by scale being less useful, new techniques or architectures (such as NXAI’s xLSTM4 or Liquid AI’s LFM), that can bring additional improvement through efficiency, will be explored thoroughly.

As the quantity of training data matters less, the pivotal determinant of performance will likely be data quality. Any proprietary data sources will drive a step change increase in performance. Businesses that help improve data quality or offer federated learning to enable secure access to otherwise unavailable sensitive/private data will become critical.

To complement this shift in priorities, we will see new benchmarks implemented to judge the models we use. These could be things like ethical deployment, efficiency, and user experience.

An increased priority will be placed on AI applications that are highly tailored for specific use cases and user workflows.

We could also see users favouring inimitable solutions crafted specifically for their workflows over general-purpose alternatives. If the flagship one-size-fits-all LLMs are no longer as far ahead of the pack as they once were (since the rate of performance improvements will likely decrease), we can expect users to prioritise salient improvements in workflow alignment. This could manifest as users opting for solutions like PandasAI for tasks like data analysis and Jasper AI for marketing.

Impact on fundraising and capital markets

We could potentially see the most interesting AI companies raising smaller (and by smaller I mean less insanely large) rounds. This logic stems from the fact that achieving best-in-class performance may no longer require billions of dollars to scale these models. Albeit, given human nature, VC fund dynamics, and an abundance of capital this is probably unlikely.

If we are forced to use alternative methods to drive superior AI performance, ones less directly tied to higher costs, we could also expect more consolidation around top company performance. No longer will companies need billions to become competitive. However, just because they won’t need billions to get to top tier performance doesn’t mean they won’t raise it. If your closest competitor raises a billion you probably will want a billion as well, if not to use for scaling LLMs than for everything else that comes with building a business in one of the most competitive markets.

What this could mean on a global scale

One of the most interesting turn of events could be how this positions the global AI landscape. We’ve already seen that US sanctions have really not been able to hinder China’s ability to produce high quality performant AI models. In fact, if anything, the limitations placed - such as U.S. export controls on advanced semiconductors and GPU chips - have forced China to be resourceful and to innovate even more. An example being China’s Wudao model - a highly performant 1.5 trillion parameter creation - that uses efficiency-focused training methods to minimise reliance on U.S.-made GPUs.

With AI innovation slowing down in the US because of limits on how we can use known resources and techniques, China may be better positioned to out innovate the US with scrappiness and the techniques they’ve had to develop to deal with existing resource constraints.

Why this could be a good thing

The true outcomes will remain to be seen. But this could end up being a better thing for investors, AI model competition, and at the end of the day consumers. We didn’t even mention that a potential forced slow down in AI performance improvements could provide the opportunity to establish long-overdue safety measures - an area we have largely overlooked.

Taking the time to think about things like advancing interpretability techniques to better understand how model decision making works or putting into place the right regulation could have literal existential scale upside in the long run.

With a change in benchmarks and priorities, metrics like energy efficiency (with hugely positive externalities) could become the new competitive edge. A focus on designing models that consume less power could have a favourable environmental impact.

Ultimately, the plateauing of scaling laws may actually lead to a more sustainable, innovative, and equitable AI landscape. Instead of sprinting blindly to an undefined finish line, we now have the chance to look up and figure out where exactly we are heading - and if that destination is one we want to reach at all.

But really, what did Ilya see…

Great piece Alex! I hadn’t heard about Ilya Sutskever’s comments before, but the way you’ve laid out the implications for the AI world is really thought-provoking.

An interesting article came out yesterday in the Financial Times (https://www.ft.com/content/e91cb018-873c-4388-84c0-46e9f82146b4), where OpenAI’s CFO highlighted that “in 74 days (since June), we put ten billion of liquidity on the balance sheet. […] We’re in a massive growth phase, it behoves us to keep investing. We need to be on the frontier on the model front. That is expensive.”

Considering your analysis Alex, I can’t help but ask myself… why would it still be that expensive? The classic trifecta - chips, data, and energy - comes to mind.

You mentioned that energy efficiency could become a major focus, which aligns with these changing priorities. As for data, it might indeed take a backseat in pure training efforts, with quality taking precedence over quantity.

And chips? That’s where it might get intriguing (and indeed expensive). OpenAI is reportedly working with Broadcom and TSMC on its first in-house chip and investing heavily in building clusters of data centers across the US (https://www.reuters.com/technology/artificial-intelligence/openai-builds-first-chip-with-broadcom-tsmc-scales-back-foundry-ambition-2024-10-29/).

This suggests that while the liquidity these companies are amassing may not be necessary for funding superior AI performance, it could be used to build a strong infrastructure that cements their positions as first movers. If that’s the case, smaller AI players looking to "create tailored solutions for specific workflows," as you put it, could face significant challenges competing with the scale and resources of these industry giants. I completely agree with you that “achieving best-in-class performance may no longer require billions of dollars to scale these models,” but staying competitive as the rules shift away from data-focused strategies might still demand it.

Let’s see how things unfold, but I really share your hope that we’ll start seeing more smaller AI players emerge!